IV) Completeness & Preservation

For a long time, geoscientists asked themselves the question of the continuity versus discontinuity of geologic events:

Are the sedimentary records the result of more or less continuous geologic processes, or are they associated to extraordinary processes, which take place in a spasmodic way?

Since the 18th century, geoscientists have given very opposite answers. Presently, the majority of them consider that the sedimentary records are incomplete and separated by important periods of non-deposition during which nothing happens. In spite of that, it is surprising to see that some geoscientists continue to forget in their stratigraphic models the long periods of non-deposition during which nothing happens. In stratigraphic sections, the time-duration of hiatuses (by non-deposition or erosion) is generally much important than the deposition-time of the preserved sediments.

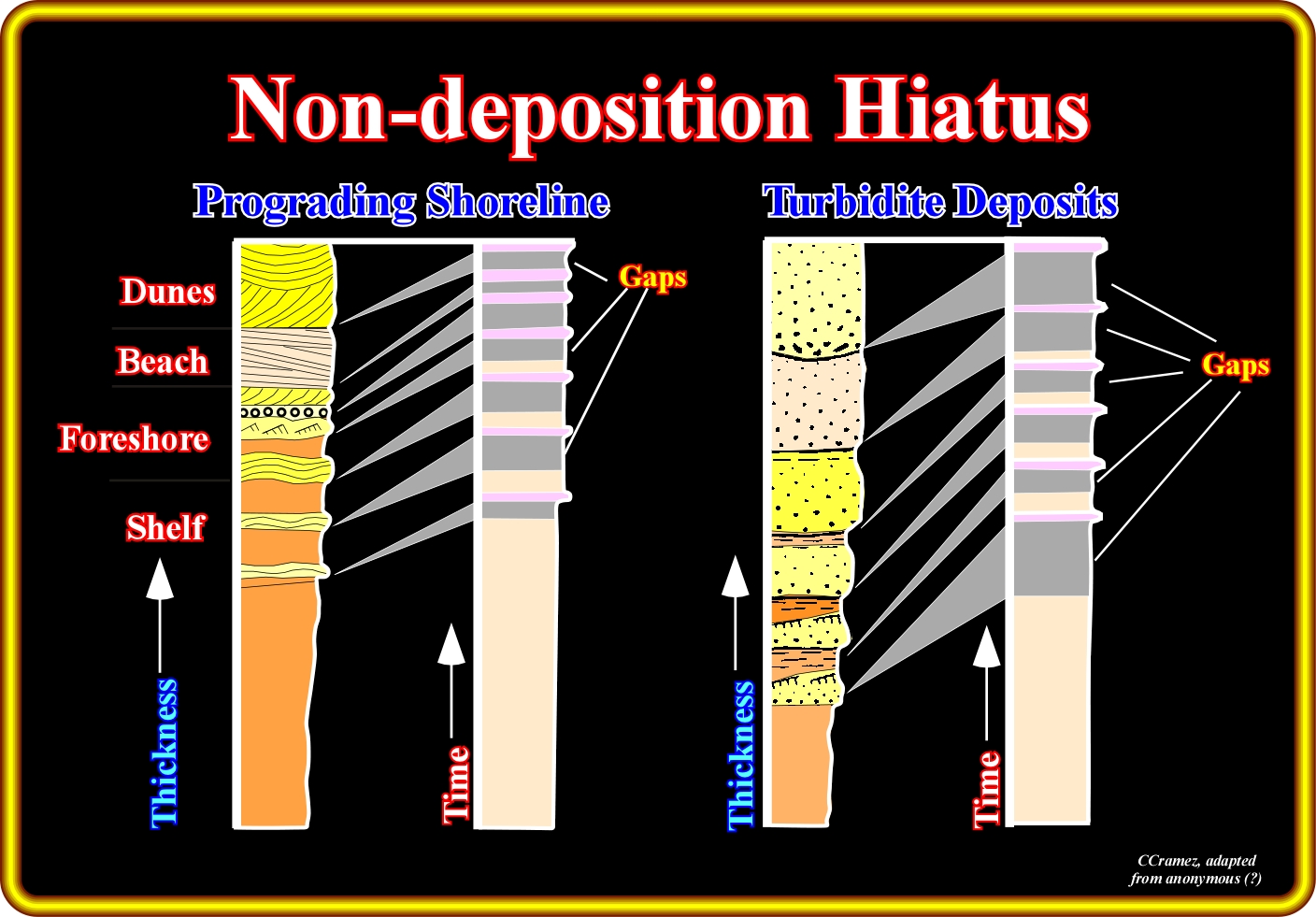

In these geological columns and particularly on their upper parts, the periods of non-deposition are much longer than the periods of deposition. In a prograding shoreline area, as illustrated above, a large number of geological events took place, but the associated deposits are not preserved. They were eroded. They were replaced by significant erosional-hiatuses. In turbidite depositional systems, erosion is insignificant. The hiatuses are non-depositional. The sedimentary preservation is much higher than in the prograding shoreline areas, however, conversely the completeness is much lower.

Stratigraphic sections are just local archives of the geologic history (Sadler, 1982). The records of these archives are the sedimentary layers. They are deposited in succession and, generally, numbered according to their thickness rather than their deposition-time (period during which there is deposition). Nevertheless, geoscientists know, since long time, that stratigraphic sections contain numerous hiatuses induced whether by the erosion or non-deposition.

On this particular subject, three important questions come always to the mind of geoscientists :

1) What is the deposition-time of a single sedimentary bed?

2) What is the total-time of deposition of a stratigraphic section? (span of time between the bounded unconformities)

3) What is the ratio between the total-time of a section and the actual deposition-time of its beds?

The answers of the first two questions are relatively easy.

- Concerning the first question, one can say that :

1.1) A lamination of a beach deposit is deposited in about one second ;

1.2) A HCS bed (“hummocky cross stratification“), characteristic of storm deposit, is deposited in few minutes ;

1.3) A turbidite layer is deposited in few hours ;

1.4) A flood deposits, such as the Scablands in Canada (deposits and erosions associated to the floods induced by the break-up of the lakes’ retentions at the back of Plio-Pleistocene glaciers), can be deposited in few weeks ;

1.5) A glacial varve is deposited in one year ;

1.6) A centimetre of a pelagic sediment is deposited during about 100 years.

- Concerning, the second question, one can say that :

2.1) A continental encroachment stratigraphic sub-cycle has a time-duration ranging between 10 and 20 millions years (Duval et al., 1993) ;

2.2) A continental encroachment stratigraphic cycle has a time-duration ranging between 100 and 300 million years (Duval et al., 1993).Sadler (1982) suggested that the deposition-time is conversely proportional to the rate of deposition. Higher is the rate shorter is the time. From such a hypothesis, it follows that the majority of the periods of non-deposition escape us. The sedimentary records correspond to short periods of terror separated by long periods of tranquillity where nothing happen (Ager, 1982).

The last question, that is to say, what is the ratio between the total-time of a stratigraphic section (span of time between the bounded unconformities) and the deposition-time of all its preserved beds, it is more difficult to answer. It put forward the problem of the completeness of stratigraphic section, i.e., the deposition-time and the preservation of the beds composing a section. The preservation of a stratigraphic section generally depends on :

(i) The amplitude ;

(ii) The frequency of the stratigraphic events ;

(iii) The depositional environment.The stratigraphic events more represented in the stratigraphic records are those that have a normal or weak frequency, i.e., those that take place sporadically. In this sense, basin floor and slope fans strongly contrast with pelagic shaly intervals, which separate them. The pelagic intervals are stratigraphic events with normal frequency, whereas turbidite deposits are instantaneous low frequency events. Let’s see an example:

a) Suppose an interval composed by 100 turbidite layers and 100 of pelagic clays ;

- Each turbidite layer has a thickness of 10 centimetres ;

- Each pelagic layer has a thickness of 5 centimetres ;

b) The total thickness will be 1500 meters ;

c) Assuming an average depositional rate of the pelagic clays of 5 cms / 1000 years, and

d) An instantaneous depositional rate for each turbidite layer.One can deduct :

(i) The total-deposition time is 100 000 years ;

(ii) The frequency of turbidity currents is of 1000 years (1/1000 of the total-deposition time) ;

(iii) The completeness and preservation of the pelagic clays is 1 ;

(iv) The completeness of a turbidite layers is almost zero (0), but its preservation is 1, i.e., almost total (Dott, 1983).

In this example we can conclude:

Two thirds of the sedimentary interval were deposited by instantaneous events with a low frequency (one event each thousand years). In 10 My, ten thousand (10.000) instantaneous turbidite events were deposited in a section of 1500 meters. In other words, what seems impossible at the human scale becomes, on a geological scale, possible and the improbable becomes inevitable (Simpson, G. G., 1952).