As illustrated, the regional tectonic context of Muzo and Chivor areas is quite different of tectonic context of Cusiana area, which is located in the Llanos foreland (“avant-pays”), while Muzo and Chivor are located in the fold belt. Lower Cretaceous sediments are outcroping in Muzo and Chivor areas, while Tertiary sediments outcrop in Cusiana area ( Lower Cretaceous sediments were not deposited). The Eastern Cordillera corresponds to an tectonically inverted sedimentary backarc basin of Jurassic-Late Cretaceous age filled by thick restricted and open marine sediments. In the Cusiana area the inversion is just partially since a tectonic null point (reverse geometry above, but normal fault geometry below) is always visible in reactivated fault planes. In other words, in Cusiana area, the temperature of the Mesozoic sediments never exceed 110° C.

As Lower Cretaceous sediments outcrop in Muzo and Chivor areas, geoscientists must calculate the amount of erosion in order to determine the temperature of emeralds genesis, since the thermobarometric data for emerald is 290 - 360° and 1Kb (Cheilletz et al., 1993). The burial temperature calculated from geological data (see A-B geological cross-section in Colombian Regional Cross-Section and next plates) is around 135° C at 4500 meters depth (Hebrard, 1985). If that is so, it is necessary to find an additional temperature input (165-225°) within the Lower Cretaceous sediments at the Eocene Oligocene boundary to provoke emerald-pyrite-calcite. Several conjectures have been advanced to explain such additional input as a possible synchronous magmatism or an heat conduction implemented during halokinetic (salt) diapirism (the fluids associated with the emeralds are hyper-salted and the formation temperature are estimated at 300°C).

This tectonic cross-section, as well as the stratigraphic cross-section illustrated in after next plate, corroborates the tectonic inversion of the pristine Mesozoic backarc basins (strongly thickening inward) and the pre-Andean sediments (more or less isopachous), which are depicted in green. In central part of the basin the inversion is total (the geometry of all fault planes is reverse). All faults have a reverse geometry, even if some of them were normal faults (syn-sedimentary Lower Cretaceous). In the border of the basin (Llanos foreland), the tectonic inversion is just partial, since just few faults were locally reactivated. In stratigraphic terms, this cross section suggest thick Lower Cretaceous sediments, in the central part of the basin, and a total absence or just few meters in the foreland and Llanos basin. In other words, the Lower Cretaceous carbonaceous siltites, which host the emerald deposits do not exist in Cusiana area (see plate 10). In spite of the fact that the amount of erosion induced by the relative sea level fall (mainly created by uplift induced by the tectonic inversion) is difficult to calculate (as well as the thickness of pre-Andean deposited before the inversion), several geoscientists (Hébard, F., 1985) have suggested an insufficient burial temperature to explain mineralization. A minimum of 6 000 m (excluding erosion) of vertical transfer can be deduced, which is responsible for the tectonic inversion of the Jurassic-Cretaceous backarc basin and for the outcropping host rocks of the emerald deposits. Note that the tectonic map, illustrated above, as well as the geological cross-section explain the global tectonics of the Oriental Cordillera and the more likely genesis of the emeralds, but are largely inadequate two support a exploration-production of the emerald deposits. A much more detailed and exhaustive geological maps and cross-section are require as illustrated later.

This stratigraphic cross-section illustrates the stratigraphic columns of Cusiana and Muzo-Chivor areas. Unambiguously, the Lower Cretaceous sediments were never deposited eastward of the major normal fault bordering bordering the deep backarc basin. The emerald host sediments, as depicted, are mainly calcareous shales and sandstones rich in organic matter, which is necessary for a thermochemical reduction of the sulphate rich brines.

Before outlining the more important problems related with the emerald exploration-production in the Oriental Cordillera, we end this first part depicting a set of diachronic cross-sections summarizing the geological evolution of the Oriental Cordillera: (i) Jurassic - Early Cretaceous phase rifting of the backarc basin ; (ii) Early Cretaceous - Campanian thermal phase of the backarc phase ; (iii) Maastrichtian .- Paleocene accretion and early foreland basin ; (iv) Middle Eocene - Middle Miocene pre-Andean Foreland basin ; (v) Middle Miocene tectonic inversion and (vi) Middle Miocene recent Andean foreland basin.

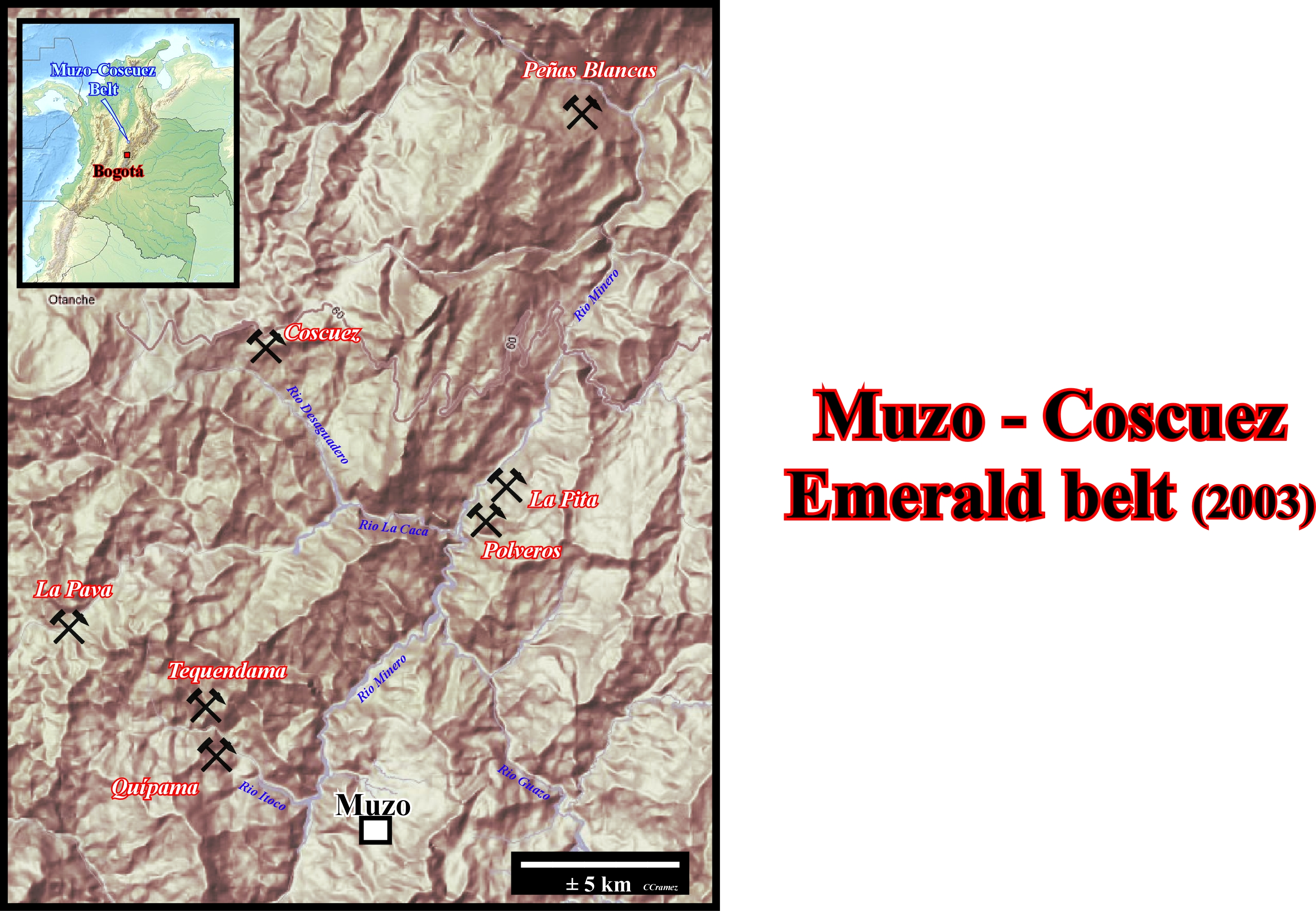

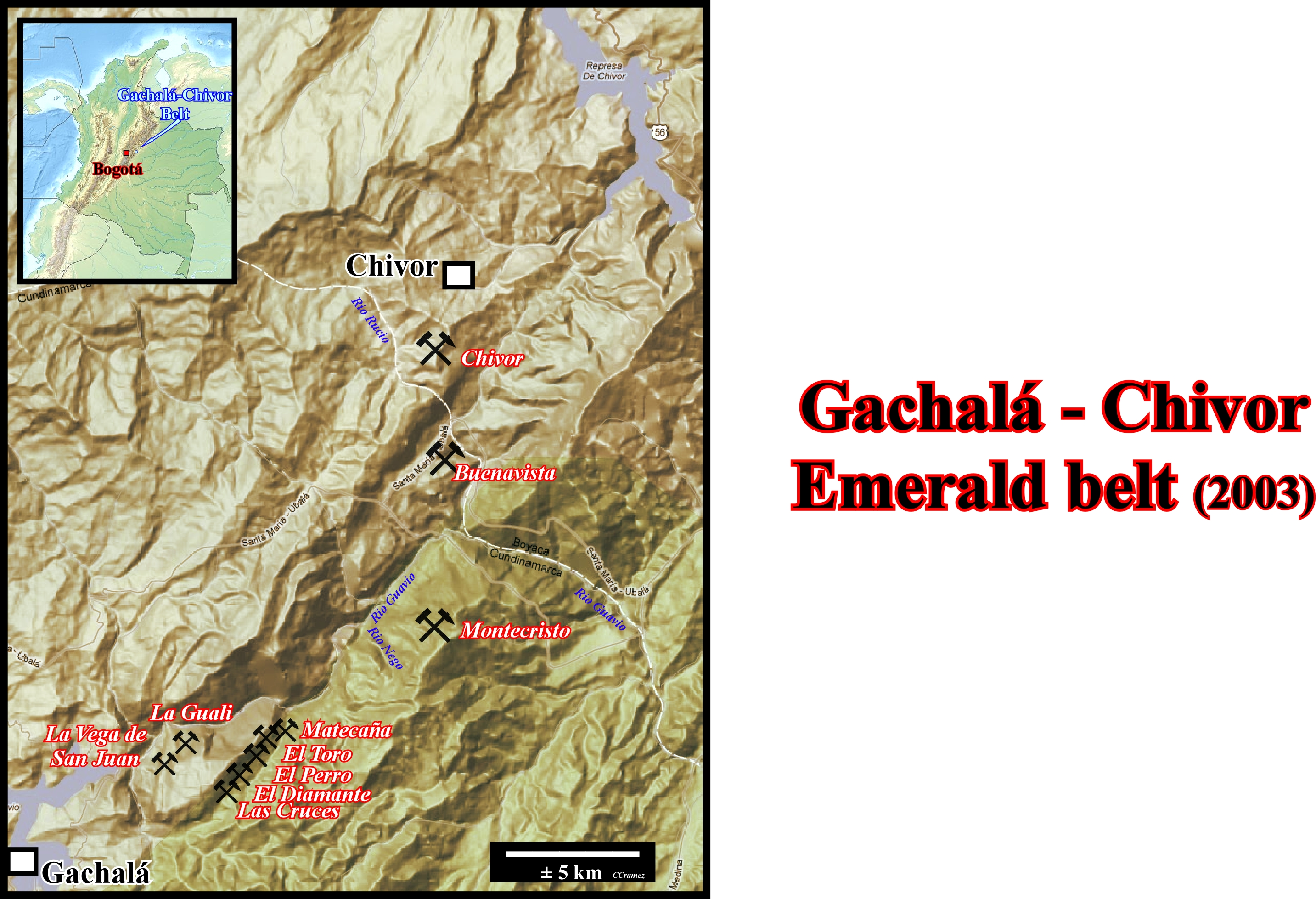

In Oriental Cordillera there are two emerald belts : (i) Muzo - Coscuez, in the western part of the Cordillera, and (ii) Gachalá- Chivor, in the eastern part. In the western belt (Muzo-Coscuez), the principal emerald mines are : La Pava, Quipama, Tenquendema, Ploveros, la Pita, Coscuez and Peñas Blancas. In the eastern belt (Gachalá - Chivor), the prinicipal mines are : Gachalá, Montecristo, Buenavista and Chivor. In the Chivor mine are included the following sites : San Gregorio, Porvenir, Klein, Oriente, San Franciscio, Guali Alto, Guali, Palo Arañado, Quebrada Negra (between the Guavio and Batá rivers) and Agua Blanca (northward of the Batá river).

1) The Muzo-Coscuez emerald belt includes the mines of Muzo, Coscuez, Peñas Blancas and Pita. All other deposits are probably non economical. 2) This belt currently produces almost all Colombian emeralds. 3) Yacopí mines, located 35 km west of Muzo are no longer officially exploited (2002). 4) Around 1992, some 30000 guaqueros (independent miners) searched for the cuttings discharged into Itoco river by the bulldozers of concessionary companies. They have left the region after the abandonment of open pit mining. 5) Presently, this emerald belt is operated and explored almost exclusively by wells and galleries after open pit mining intensive exploitation, which gradually eroded the mountains and filled the valleys (quebradas). 6) Muzo area comprise Tenquema and Quípama mines, which are separated by a few hundred meters and located on both sides of the Rio Itoco. 7) Tequendama mine was exploited (2003) by two vertical access shafts (Tenquendama, Puerto Arturo), as well as, by horizontal access galleries (drift mining) : Volveré Trenta y Cinco, Chucaros and El Retorno. 8) Quípama mine was exploited (2003) by Palo Blanco, El Aguardiente, El Masato vertical access shafts and Pablo Sanchez and Matefique access tunnels, as well as El Zincho open pit mining. 9) The production of La Pava access tunnel, located on the SW boundary of the concession was sporadic. 10) Polveros was in activity since 1993. However the emerald production was any more significant in 2003. 11) Pita was exploited (2003) by two access tunnels (Prominas de Zulia and Santa Rosa) with a significant production. 12) In Coscuez, among the three hundred tunnels, just few were in activity in 2002 (La Paz, El Diamante, La Marranera, Gavilanes, S.A. Sufrimiento, La Tabla and Tecnimur. 13) Peñas Blanca located, in Tambrias mountain, was actively exploited but clandestinely (1960-1980). Its isolation and the quite compact host rocks (limestones) make mining difficult.

1) Chivor, Buenavista, Montecristo and Gachalá (La Vega de San Juan, La Guali, Las Cruces, El Diamante, El Perro, El Toro, Matecaña), located in the Guavio valley, form the Gachalá - Chivor emerald belt. 2) Chivor mines (Somondoco) are exploited by open pit mining, vertical and horizontal access shafts. 3) The main active sites, in Chivor, are : Alto de la Chula, El Simnai, La Gualí, El Oriente, Klein, El Coliflor, Cuatro, Montecaña, El Acuario, Gravilanes, La Guala, Las Palmas, San Francisco et San Gregorio (see later). 4)The mines of Buenavista, Montecristo and Gachalá are located in Cundinamarca department. 5) Near Buenavista, the sites of Mundo Nuevo are not exploited at large scale. The concessions of Vega de San Juan, Las Cruces and El Diamante are the more important mining sites. 6) In 1993, Gualí mine produced large amounts of massive emerald in blocs of more of 1 kg. 7) Macanal and Achiote sites, located northward of Chivor on the banks of the artificial lac of the Garagoa river (Chivor dam), were abandoned. 8) The emeralds produced on this belt have, generally, few internal defects and the color is zonated along hexagonal prisms.9) In XVI century, the Somondoco mine, between Sinai and Rucio rivers, was exploited by the Chio tribu, before the Spaniard arrived to the area. Historically speaking, it is interesting to note that in 1953, around 15 km southwest of Chivor, emeralds were found by chance near the farm of La Vega de San Juan. After such a discovery, the area was intensively explored and exploited and nice emerald were founded. The peak of production was reached in 1970. 10) In addition, following the impoundments of the Guavio dam, in 1989, to avoid that the mining debris fill up the dam (Colombian authorities), just rudimentary exploitation by vertical an horizontal shafts, controlled by Quintero and Caranza families, were tolerated. 11) Since 1998, the guerrilla (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia, FARC) invested this region, since it is the natural bypass between the oriental plains (Llanos) and Bogotá.

GoNext

GoNext

Send E-mail to carloscramez@gmail.com with questions or comments about these notes .

Copyright © 2012 CCramez

Last modification: December, 2014